Excerpt from Chapter 1: Orchard Street

July 15, 1899

The last day of my youth began with the shatter of a plate and the piercing scream of an infant. I awoke in my small tenement on 43 Orchard Street before the sun had barely stirred. The air filtered in through cracks in the wall and was bitter cold, but the upcoming hot summer day would change that soon enough.

It was Friday, and my father was already roused and dressing for work. He glanced down at me with a smile. “Guten Morgen.”

“Good morning,” I mumbled back in English.

“Now, up,” he said sharply.

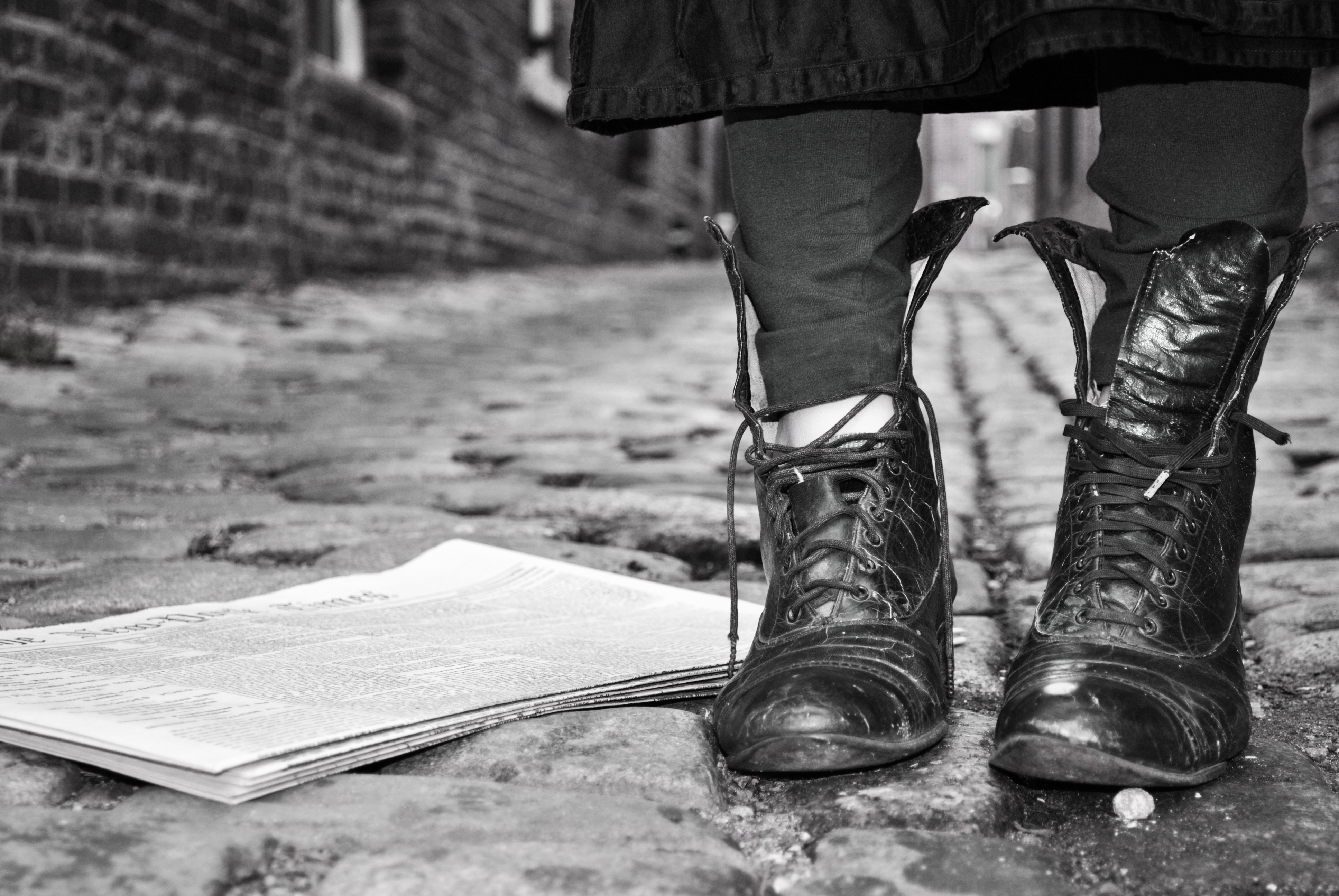

I exhaled, bit my lip, and pulled back the covers, exposing myself to the frigid air. I slipped on my rubber-soled boots, a gift from my mother before she died. She once told me they represented equality and would lead me places beyond my wildest dreams, but all they did was constantly break apart at the seams, forcing me to wrap the laces around the bottoms to keep the soles on my feet. I often searched for ways to slip them off. Maybe my bare feet didn’t represent equality, but they felt freer than being bound in broken shoes.

“Keep them on today,” my father stressed. “Muss immer getragen werden.”

Every day my father felt he needed to remind me to keep my boots on “at all times.” But at the age of twelve, I knew that my father wasn’t truly giving reminders—he was giving instructions.

As usual, deafening screams interrupted us. Our tenement was always filled with the noises and smells of Mrs. Krol, the Polish widow with whom we boarded, and her five children. The bitter woman often lingered close to our half of the room, bouncing her wailing child on her hip to calm him.

Mrs. Krol frequently pleaded for me to take the screaming boy in my bed since there was no room in hers. She sometimes bribed me with a Liberty Head nickel, but I would decline. No amount of money was worth having such shrieks so close to my ear.

That morning I didn’t have a job waiting for me. The day before, the Joseph Luby tailor shop suffered a terrible fire, nearly killing three workers. This was the first day since my mother’s death that I was not spending at the shop.

I leaned forward behind the calico sheet that divided our small tenement so that I didn’t have to see Mrs. Krol struggling through her morning routine. “I knew it was going to happen,” I said softly.

“Was, Elsie?” Papa asked in German, slicing a stiff loaf of bread for our breakfast.

“I knew the fire was going to happen. There were always spare scraps on the floor near the gaslights. There was only one exit for the girls and one small bucket of water. I should have said something.”

Papa kneeled down and took my hands in his. “It’s not your place to get involved in such matters. You would have been let go for saying such things. There will always be someone else for that. You stay quiet and keep to yourself. It’s the only way to keep your job.”

I always believed what Papa said, but there was something inside of me that knew my silence in that instance had been wrong.

“Ja?”

“Yes . . . ,” I nodded in agreement.

“Good, so you come with me to the railroad today. There are flower girls who work outside Vanderbilt. You will ask them where you can do the same. But keep those boots on!” he scolded.

The sun was now peeking over the tenement across the street, and the warmth was creeping across the laundry line toward our window.

“Come.” He lifted me up off the bed and nestled me into his six-foot frame. He was my protector and all I had.

“Dietrich, if the child is not going to work today, she should stay here and help with the small ones,” Mrs. Krol demanded.

I cowered. Her stare was sharper than my father’s razor. “We pay to board,” my father said. “Unless you desire to pay her for her time?”

Mrs. Krol scoffed. She would never pay me. Too often she treated me like a child. I was twelve, but because of my small frame I still looked ten, so people often treated me like a child.

“Well, that settles it.” Papa winked as he whisked me out the door.

In the dark hallway of the tenement, I stepped over two young street traders curled up along the wall. They were no more than eight years old and reeked of sewers and spoiled milk. I tried to cough out the smell. I wasn’t sure if the stench came from the two boys or if it was the normal smell of the hallway. In our tenement, most of the time it was hard to determine where unpleasant aromas came from.

“They shouldn’t be sleeping here,” I mumbled to my father.

“Elsie, quiet,” Papa scolded.

Papa was right. I knew I had no place to look down on them, but I hated their crass voices and the freedom they flaunted. We paid four dollars a month for our half room shared with Mrs. Krol. These boys paid nothing and still received suitable shelter in our hallway.

In fact, as we approached Vanderbilt and 42nd, a similar newsboy was yelling on the street corner, crowing on about his wares. “Man found dead by railroad. Crushed skull! Killer on the loose!”

I sped up to escape the shrill of his call, but the front lip of my rubber sole caught on the pavement and bent backwards, sending me diving to the ground. Immediately a hand scooped me upright.

“Thank you, Papa.” I brushed myself off. Yet when I looked up, it was not Papa’s face that peered down at me but the shouting newsboy’s wide, toothy grin.

“Ya all right, lady?”

“Fine.”

He let out a light laugh. It was carefree. I clenched my teeth, reminding myself to be polite, and forced a smile as I scurried to join my father a few paces ahead.

Curious, I looked back at the boy who had already returned to hawking the daily paper. I noticed he wasn’t a boy at all. Likely fourteen, he was tall with messy brown hair tucked under his cap. His face had soft features, but his wide smile wrinkled at the corners with a simple right dimple. It held the most weight on his face, drawing an admirer right to it. No dirt had collected around his brow like the other newsboys, but it was still early in the day. Most unusual, though, was a book tucked neatly in the rear of his trousers between his pants and the small of his back.

Suddenly, he peeked over his shoulder and caught my stare. I flinched. But just as I was about to turn away, he offered me one more wide, soft grin.