Excerpt from Chapter 5: Vincent Boys

July 18, 1899

Morning came quickly. I was pleased that I awoke naturally and was ready to go when Grin tapped on the hatch. He was still in the same clothes from the day before, stained and dirty.

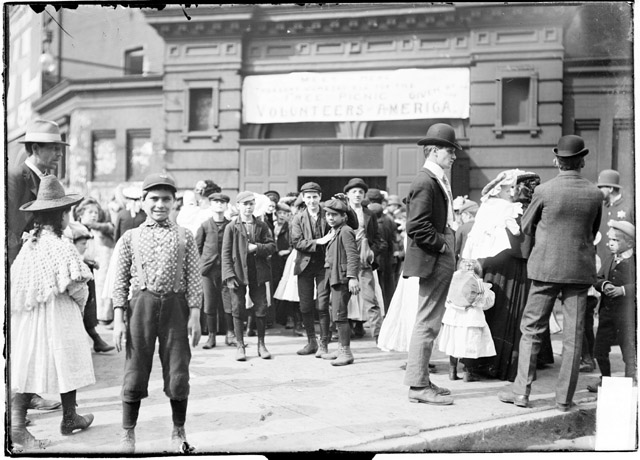

We didn’t have to go very far. St. Paul’s Chapel was situated right at Park Row, or Newspaper Row, where all major newspapers had their downtown offices. Even though the sun was barely up, there were loads of newsboys gathered, ready for the day.

“There’s lots of papes to sell, but I only sell the Journal. One of the yella kid papes,” Grin explained.

“Yella kid? What are the yella kid papes?”

“Like yell-ow.” Grin let the o roll off his tongue in an effort to be proper in pronunciation.

“Oh, yell-ow,” I enunciated.

“So ya know the best papes in New York, Joseph Pulitzer’s the World and William Randolph Hearst’s the Journal?”

I nodded in agreement, although I really had no clue.

“Well, these men hate each other,” Grin explained further. “So a couple years ago, Hearst stole away the popular cartoonist who drew Hogan’s Alley from Pulitzer to draw the yella kid for his pape. Ya know about it, right?”

I shook my head.

“Ya don’t know about the yella kid? Shaved head, lots of mischief?”

I shook my head again.

Grin continued, “Ah, well, the comic was printed in color, and the kid was all dressed in yella. Well, Pulitzer kept printin’ Hogan’s Alley even after Hearst started printin’ the his comic he named The Yellow Kid. Both printin’ the same comic. So, ‘yella kid papers’ was the name some guy gave the two papes. I never thought the comic was any good, myself.”

A bell tolled, and the gate to the paper’s circulation office opened.

“I only have my nickel,” I said to Grin as the line got closer and closer to the delivery window of the New York Journal.

“If we’re partners, we’ll both work to sell the papes, and you pay me back the cost of what ya sell.”

I wanted to ask why Grin was helping me, but I was afraid I wouldn’t get a truthful answer. At first thought, maybe he figured having a girl beside him would help him sell more papers, but Grin was too good of a newsie to need my help.

We approached the window of the counting room.

“Hundred papes.” Grin smashed down sixty cents on the counter. The manager behind grunted and shoved the papers toward him.

“A hundred?” I asked as we walked away.

“That’s just the morning pape,” he explained.

It seemed like all boys knew Grin as they shouted “ ’Ello!” and “Mornin’!” when we walked past. But he kept to himself, just nodding to each one who greeted him.

“Do you prefer working alone?” I asked.

“Nah. Depends.”

I tried not to appear eager as I followed behind him.

“You don’t go to school?”

“School is here on the street. Why be locked up during the best time of the day?”

Grin walked quickly, moving up and across the street, passing the morning commuters with ease. He seemed like he had a plan, and I didn’t question it.

“First thing you want to know about sellin’, ya have to have a spot. Boys, and girls for that matter, are real territorial around here. Each gang has their spot. Most of the newsie girls are out by the bridge or up by the park.”

“Are those good spots?”

“Some days. Morning is best at Wall Street, no two ways about it. Afternoon is best anywhere near the food. At night, it’s the theaters. I keep moving, and since I have no one to depend on, no place to be, it’s easy for me.”

“You got me now.”

He stopped. “Ya right, but you’re like me. I see it in ya—you’ll stand on your own soon.”

As much as I wanted to take that as a compliment, there was a part of me that didn’t want to leave Grin. I knew that if my poor attempts at selling the night before continued, maybe he wouldn’t release me from training too quickly.

The businessmen of Wall Street emerged from the dawn like the mosquitoes in Chicago. They moved hurriedly, clouding the sidewalks as they rushed toward the white-columned buildings. Grin flew into action.

Unlike the smaller newsboys, Grin didn’t shove the papers in the face of the men. He stood in one position, raised it high, and with confidence belted out the news of the day. His calm presence seemed to attract the men, who were turned off by the brash approach of the other newsboys. They swiftly bought the paper from Grin before continuing along their way.

As the chaos wore down, the other newsies started to take notice of me working with Grin.

“Who’s the girl?” one sneered at Grin.

“Never ya mind.” Grin shooed him off.

“She with you?”

“Yeah, what’s it to ya?”

“I wouldn’t be splittin’ papes, ‘specially now.”

“What do ya mean?”

“The Long Island boys, didn’t ya hear?”

Grin shook his head.

“Strike fever, first Brooklyn trolley strikers and now Long Island with newsboys.”

“Strike?”

“Yes, um, I’m just tryin’ to sell as many papes as I can today before it hits,” the young boy said as he turned and ran off to a man stepping out of a carriage.

I looked at Grin. He was deep in thought.

“I’ve never seen you think so hard,” I said lightly.

“We got to go.”

“Where?”

“Vincent’s,” Grin said to himself.

I ran to catch up to Grin, who was already on the move. I remembered his mentioning the Vincent boys to the boy he hit but had no idea what it meant. As we rounded Broadway onto Warren Street it became clear where we were headed: St. Vincent’s Newsboys Home.

The building at 53 Warren Street was just two blocks from Newspaper Row. It looked like a religious boarding house, similar to the asylum. I hesitated.

“It’ll be fine,” Grin laughed. “We won’t go inside.”

Grin walked around back to the alley. Sure enough, there was a band of six boys. They looked like they ranged from age ten to seventeen. Some held their papes while others let them rest at their feet. A pair of dice sat atop a barrel in the middle of them untouched. All looked in a hurry, ready to rush off to work if not for pressing business. I wondered what it was about these particular boys that was enough to scare Rat off when Grin mentioned them.

The one leading the conversation had red hair and a black eyepatch over his left eye.

“The Long Island boys had it right. The deliverymen was cheatin’ ’em, givin’ ’em a stack with a few papes less than their order. They had to soak ’em,” said the boy with the eyepatch.

An older kid, probably sixteen or seventeen, with large eyebrows and rather clean clothes leaned forward. “We don’t need a strike. We all gotta eat. We all gotta pay board.”

“But Abe, ever since de war, it’s still six cents a ten. News ain’t the same now, yet we’re still payin’ the same,” said the boy sitting next to him, who looked like one of the oldest in the bunch

“I know what we pay, Jim,” sneered Abe.

“It’s Hearst and Pulitzer too. Both are stickin’ to their price,” added the one with the eyepatch.

He took notice of Grin.

“Grin! Just in time.”

“Kid.” Grin spat in his hand, and the two shook. Kid’s smile faded when he saw me.

“Why de dame?”

I didn’t say anything.

“Why the strike?” Grin countered.

“Boots is takin’ all his boys up to City Hall Park tomorra. Dave too. They’ll make a decision there.” Kid took a seat without recognizing my presence. I kept standing.

“We need to stand on our own no matter what,” chimed in a boy no taller than four feet. I figured he had to be way too young to be working with these boys.

“We always do, Indian” Grin said.

“It sounds like all gangs will be on their own, even if we do strike.” Kid appeared to be the leader of the Vincent boys, and they hung on his every word.

“Will there be enough of us?” Grin challenged.

“There’ll be a hundred boys at Park Row. That’s enough to strike. I say we Vincents lead the cause, rally the others around us,” another boy added.

“We ain’t leadin’ anythin’ yet Fitz.” Kid said, clearly annoyed by him. “But imagine Grin, if de Brooklyn boys are behind this, even Jersey.”

“What about the cops?” Grin took the dice off the barrel between the boys and shook it in his hand.

“They’re all tied up with the trolley strikers. They don’t care ’bout us,” the smallest boy interjected.

Grin nodded, taking this in.

“So, yer with us?” Kid asked.

Grin rolled the dice: snake eyes.

“I’m with ya.”